By Lotte Lewis

In the passivity of belonging to an order, he was the first disappearing term.

She carried on in the face of the meat market bombings, the conditions in the camps. She carried on amid the Golden Dawn slogans painted across the busiest bridge of the city, the mass evictions, the tented occupations of Syntagma square, the murder of Zak Kostopoulos, the masculine fronting in the squats, the mass hunger strikes, the tightening of passage into Europe, the anniversary riots for Alexandros Grigoropoulos, the pensioners hurling flowerpots at cops from their balconies, the mass raids, the growing number of Airbnbs, the burgeoning graffiti tours, the smashing of cars with diplomatic plates — the one that turned out to be Palestinian, the mass fingerprinting, the YPG posters covering every other wall in Exarchia, the protests in the camps on the islands, the mass beatings, the continuation of Operation Xenios Zeus under other guises, the poetry magazines distributed in squats and social centres and at bookfairs, the Macedonia name-change deal, the ATMs jammed with glue, the conversations about changing politics under broken streetlights and foliage and cigarette smoke, the forced deportations to Turkey, the mass arrests, the rumours of borders opening, the boats arriving and arriving and arriving — untouched by the changing seasons.

I sat at the desk and waited for her return — for the news, any news. We went to eat, to look elsewhere — out the door, down the huddled elevator, the front door, the street that led to more streets to more streets. Past the Polytechnic — carnations covering the bulldozed gate of 1973 — past the tomatoes and mangoes and peanuts spilling down Kallidromiou from the local laiki agora, the sounds of rebetiko drifting out from a late-night steki, or the chant of “We are smashing up the present because we come from the future!,” past the messages of solidarity scrawled across doorways and pavements and forearms and tree trunks. Those times I was more of a listener than a participator. Otherwise skeptical of everything but the skeptical, we were not in any position to distinguish a movement toward the inside from a movement toward the outside.

Language is what happens when we don’t feel touched. These transient border “hotspots” — gathering information, sharing information, verifying information, discussing and lamenting and sometimes displaying colossal indifference to the gathered, shared, and verified information — occurring daily, ongoing, occurring, ongoing. When we weren’t gathering, sharing, or verifying information related to here, we were refreshing screens, posting updates in group chats, checking in with one another about there — Erdoğan announcing an imminent invasion, 50,000 olive trees burned down by Daesh in Kobanî — their tanks branded with “Made in USA” — YPJ collective suicides when surrounded, Operation Olive Branch, Trump withdrawing troops from nearby areas, Operation Euphrates Shield, the US building watchtowers along the Syria-Turkey border, volunteer arrests on return, hunger strikes, YPG alliances and compromises, estimated number of international volunteers, estimated number of dead, estimated number of affected, estimated number of friends. The video of a Turkish airstrike in Afrin circulated on loop, whether or not the eyes were open or shut.

Could it have been this airstrike he died in, this very one? Habitually we climbed Strefi Hill, to the north of the city, late afternoons. She stayed up until five in the morning, writing about how “the crisis” isn’t over, about how “the crisis” isn’t actually the kind of “crisis” they are calling it, but “a crisis” of something completely different, something so deep in the trenches of crisis that we can barely recognize it as anything other than our lives. Press lists were exchanged, edits made late night and early morning. Walls were talked and shouted and whispered through. Poets abandoned their studies, and yet poems were still scratched out on the backs of exercise books and Rizla papers and Styrofoam cups and the last of the toilet roll. We talked about the past and the present and the future all in one long single sentence. Someone says, all of the civil service in Rojava are sleeping with their Kaleshnikov’s ready to be called to the front. Someone says, attacks are taking place in the forests in the outskirts of Afrin. Someone says the forests of Afrin are burning. Someone says the Syrian Armed Forces are arriving at the frontlines in Manbij. “But I do promise to be back,” writes J in her message.

We went to eat, to look elsewhere — out the door, down the huddled elevator, the front door, the street that led to more streets to more streets. These times I was more of a listener, and therefore a participator. I got the feeling that the hardening I sensed inside was growing to become more of an opening than a closing — a reaching toward all that I desired, beginning from the premise of what I did not desire, of what I no longer desired, of what I could not and might never desire. I sensed no longer did I want to mostly gather, share, verify, and discuss information, but to invent information that did not pretend to narrow the gap between information, poetry and the world, despite the growing feeling that information and poetry weren’t actually outside of the world. Night, rayless, entire. We sat there until orange hesitated to purple in the sky, and three men further down the hill put out their cigarettes and packed up their plastic chairs. I thought of the night, now, in other times, in that other country that is not a country, that is against the very idea of “a country,” and yet at times seems to resemble a country. On the walk back, I ripped down every single poster of his face I came across.

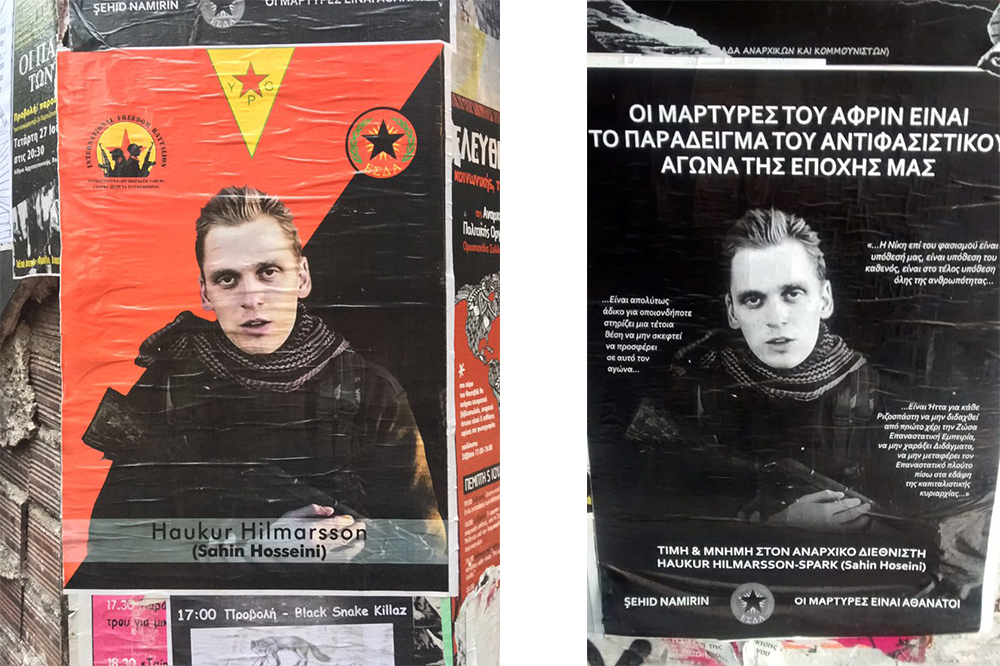

Two posters of Haukur Hilmarsson in Greek.

To say that we had seen the parts of our lives in a new arrangement would be to say that somehow we did not repeat ourselves again and again. It is a story I can barely recite, let alone follow. Each time I came across him, plastered to the walls of alleyways, of side streets, of plazas, of doorways, the discrete borders of the feeling wrapped themselves around the other feeling. Things happen. His eyes remain alive and watchful, gun strapped across his chest. The lilies shake out their pollen to the earth, though there is no body to be found; no way to know how or where or when — or if — he died, exactly:

Missing from an operation in Afrin around the second week of February 2018 and never returned. Searched for for two weeks with binoculars and in nearby hospitals, before a decision to announce dead — 18 days after he was last seen. Zero eyewitness accounts. Zero belongings found. Zero knowledge of last location. Zero remains accounted for.

It seemed like the only story, and people would repeat this story — in Reddit forums and encrypted messages and communes and bars. It was as if it was meant to outline or rehash or summarize, but in fact it resisted interpretation.

What to do with the “it” that won’t reveal itself? Proliferating I’s penetrated the continually rewritten clouds — barricading all pleasure in the plural, like attempting to fit a rose to a collision spot, or land “the people” jelly-side up. Meanwhile we watched muted videos on YouTube — flag fluttering in the background, olive trees operating in the breeze, gun shrugged over the shoulder, “martyr” written in Sans Serif across the screen. What is presence anymore? “To have a tense of is-was, the residue of it over the clear bulb of your eyes,” someone wrote in a poem. “Today — what a mocking word in this timeless cave,” someone wrote from an underground experiment on Day 156. “Testimonies remain unofficial; reports sit unconfirmed; death certificate hangs unissued,” I write in a small red notebook from her desk.

And what of those who did not choose? Over 3,844 “neutralized” in a matter of miles.

To think about it is to be the sequinned woman lying flat inside the magician’s box; to watch the saw come down, to watch its blade cut straight through the middle of you, to watch your hips fall out from underneath your ribs. G asks, “Why is the world ignoring the revolutionary Kurds in Syria?” L asks, “Did you know it was the Greek state who colluded with the CIA in handing over Öcalan to the Turkish authorities?” M says, “No man is an island, but ‘a’ man reads and writes political texts on stateless democracy from solitary confinement on an island for twenty years and a revolution unfurls.” E asks, “How come no-one went to Ukraine to fight?” M writes, “Benjamin asked us to think what a history based on the state of exception would look and feel like. Does the anarcho-feminism of the PKK suggest one answer?”

Political painting and graffiti in Athens, Greece.

Let us talk about it as though “it” ever existed. I was soaked in texts. I drew hastily on the texts of others — they put into my ears the sounds of all the people living without me. I was not in any position to distinguish one text from another — a movement toward the inside from a movement toward the outside. The texts became whole rooms, and the rooms became whole houses, and the houses became whole streets, and the streets became a yearning occupation of a city, not a country, but a city, in which lush syllogism invoked the need to seize this experience and let it become sentences. The texts became a form — the longest form, one which is still now occurring, ongoing, occurring, ongoing. In Western journalism, the quote marks around “martyr” like a barricade, like Heidegger’s cross through a word; “all language is under erasure,” the valorizing of one form of commitment over another. The words, his death, in quotation marks — reduced to language, to art, to poetry. It is through this that meaning becomes a state of constant turbulence. I want to ask, can the poem be the resistance that resembles the original violence? I want to ask, how far do these ideas spread to “the people” in Cizîrê or in a library or in a café or in a collective, or in this very room in this very building on this very street — in the city that is a city but is not a country, or at least does not desire or resemble or announce itself as a country?

The posters flesh-out gradually or at once into something quite beyond. Posters through which the so-called dead become routine, become routinized. I go to the supermarket, I go to a bar, I go to a squat, I go to a poetry reading. Never do I consider going “there.” Do I.

“Where your nonexistence was so strong,” wrote Jacques Roubaud, “it had become a form of being.” You think you are dreaming the poem. You are its dream. On the other hand, his being dead doesn’t exclude his being alive, either:

For a long time I have considered the meaning of the point of no return. In traditional politics, liberal politics, there is always a point from where you can return. You never make a full commitment to any kind of cause, not even for a limited period. You never do anything that might change your life forever.

By which how to talk about what is still ongoing? “No tenses any more,” Denise Riley writes in Time Lived, Without Its Flow, following the death of her son. The water dries up before the dark blue hyacinths are placed into the vase. A wound opens the possibility of awareness. He will come home younger, though he is undoubtedly dead. I spent too long wondering, is to heal a wound to allow what has been experienced or learnt to fade, to expire, to forget, to disappear? I spent too long wondering, is it possible to hold a wound open — just enough to allow it light, oxygen, world — to prevent from altogether numbing, without having it hurt more and more? I spent too long entering the text: a room I could go into, in which I could remember. It became a book I didn’t mean to write. I wanted it to be autobiographical but not self-referential. I wanted the book to relate to art and literature and music — calamitous paintings, overflowing with oils and pastels and homemade tinctures, radiant velvet curtains and irreverent trees. I wanted to be changed by language, but all that announced itself was the cold, metallic taste of words, neither beautiful, true or even desperate. This was not an anti-literature of life but the literature of “a” life, a living — occurring, ongoing, occurring, ongoing. It was not what I wanted to build from a life.

“One cannot write poems about trees when the forest is full of police,” wrote Brecht, but I spent too long wondering how to write poems about trees once someone had said that the forests were burning, once someone had said that there was fighting in the forests on the outskirts of the city that was a city of a canton, not a country or a nation-state; when trees were both what I needed most in this moment and when trees were nowhere to be found, him neither.

The feelings are not mine alone, though they are duly privatized:

What I fear most

is becoming “a poet”…

Locking myself in the room

gazing at the sea

and forgetting…

I fear that the stitches over my veins might heal

and, instead of having blur memories about TV news,

I take to scribbling papers and selling “my views”…

I fear that those who stepped over us might accept me

so that they can use me.

I fear that my screams might become a murmur

so that to serve putting my people to sleep.

I fear that I might learn to use meter and rhythm

and thus I will be trapped within them

longing for my verses to become popular songs.

I fear that I might buy binoculars in order to bring closer

the sabotage actions in which I won’t be participating.

I fear getting tired—an easy prey for priests and academics—

and so turn into a “sissy”…

They have their ways…

They can utilize the routine in which you get used to,

they have turned us into dogs:

they see to us being ashamed for not working…

they see to us being proud for being unemployed…

That’s how it is.

Keen psychiatrists and lousy policemen

are waiting for us in the corner.

Marx…

I am afraid of him…

My mind walks past him as well…

Those bastards…they are to blame…

I cannot -fuck it- even finish this writing…

Maybe…eh?…maybe some other day…— Katerina Gogou

“You have told me & in the telling have placed yourself above me as my keeper,” writes Anna Mendelssohn in the poem “Ordered into Quarantine.” Etel Adnan insists:

Some things are not meant to be clear, obscurity is their clarity. We should not underestimate obscurity… [it] is maybe its own light, because it shows you things. Obscurity is not a lack of light. It is a different manifestation of light. It has its own illumination.

“Seeing at the moment of, or at the time of, writing, what difference does one’s living make?” asks Leslie Scalapino. The spider cannot be frightened into a jar. “To imagine how he disappeared, how he died … it is so simple when you’re there; when you’re not imagining but remembering,” R said. Mostly I wanted to learn to endure the unknown; not as to know and then not know, but to never know to begin with — the timeline, the decision to travel north at the moment of attack, the contradictory testimonies, the nonexistent eyewitnesses, the whereabouts of belongings, the commitment — all the information and decisions and poetry that can change a story, a life — occurring, ongoing, occurring, ongoing.

Picasso said, “I didn’t paint the war but I am sure the war is in all my pictures.” But then he did paint the war. I spent too long pretending I could remember anything about those years other than pure sensation. I spent too long imagining it was conceivable to refer back to the moment of utterance (of “I”) as a way to organize narrative, story, self-experience. It is no longer possible to, even for a moment, throw my hands up in the air and think, “What can I do anyway? I could just give up.” I don’t want to lose what I learned from his decision, from his “death.” And I don’t want closure. And I don’t want to “move on.” I spent too long scared of forgetting, of learning to live with it and by which learning to ignore it, like a shadow that grows to become the breadth of a nation-state, a state that is not a state but something like a state that is also an anti-state; like when N spoke of his initial fear of being a sniper, losing that fear, and then becoming even more fearful at his lack of fear. And yet I don’t want to relive it night after night after night; to dream-see scenes of pure speculation, not remembering but imagining — to buy binoculars in order to bring closer the sabotage actions in which I won’t be participating.

“This is a message from one of you who right now is standing outside looking back,” writes J from one canton. To dare imagining: green was the forest drenched with shadows, the trees refusing to take comfort in less sky. At last, to guess instead of knowing; not about but nearby, where the centered thing breaks. Nothing but the half-truth, and the but-truth — how we try to reach one another. “There is no out there,” writes Muriel Rukeyser in The Speed of Darkness, “All is open. / Open water. Open I.” I know I’m partly somewhere else — how I miss the future, its sideways surrender. Imagine if afterwards everything can be pure sensation: sugar-fed and alive in its dismantling.

———

A note on the title: ‘Not to speak about / only to speak nearby’ is borrowed from the filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha: “A speaking that does not objectify, does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject or absent from the speaking place. A speaking that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject without, however, seizing or claiming it. A speaking in brief, whose closures are only moments of transition opening up to other possible moments of transition.”

A note on the text: Alongside that already attributed, words/lines/ideas/images have been used/developed/reworked from the writings/conversations of/with Etel Adnan, Ahmad, Alan, Simone de Beauvoir, Bechaela, Benjamín, Marianne Boruch, Anne Boyer, Cai, Anna Campbell, Julie Carr, Christianna, Clémence, Joshua Clover, Dimitra, Dilar Dirik, Eleni, Américo Ferrari, Flo, iLiana Fokianaki, Carolyn Forché, Heval Gelhat, Jean Genet, Jean-Marie Gleize, David Graeber, Veronique Le Guen, Haukur, Heiða, Lyn Hejinian, Edmond Jabès, Jamie, Jas, Jazra, Jenni, Joe, Julia, Katerina, Lewis, Lizzie, Lucy, Maisam, Nadar, Nat, Nikolas, George Oppen, Adrienne Rich, Denise Riley, Yannis Ritsos, Lisa Robertson, Roses, Muriel Rukeyser, Ruzgar, Solmaz Sharif, Verity Spott, Michael Taussig, Thabit, Uma, Wim Wenders, C.D. Wright, Yianna, Kate Zambreno, Zerin.

Photographs are the author’s own.